The nomads are settling down

Is Nomadland an Amazon propaganda flick, the triumph of an anarchopunk cult classic, or both?

Chloe Zhao’s Nomadland, considered a favorite for this year’s Oscar for best picture, is a story of an American spirit that refuses to be domesticated—and how that refusal challenges nothing about America.

Based on Jessica Bruder’s 2017 book of the same name documenting the lives of transient older Americans living in campers, the film follows 65 year-old Fern (Francis McDormand). After her factory closes and her husband passes away, Fern rebuilds her van into her new home and hits the road forever. While her family and friends pity her, offering her places to stay or money, Fern is confident with the life she’s chosen: single, transient, precarious. It reminded me of a controversial slogan apocryphally credited to the anarchist collective Crimethinc: Homelessness. Unemployment. Poverty. If you're not having fun, you're not doing it right

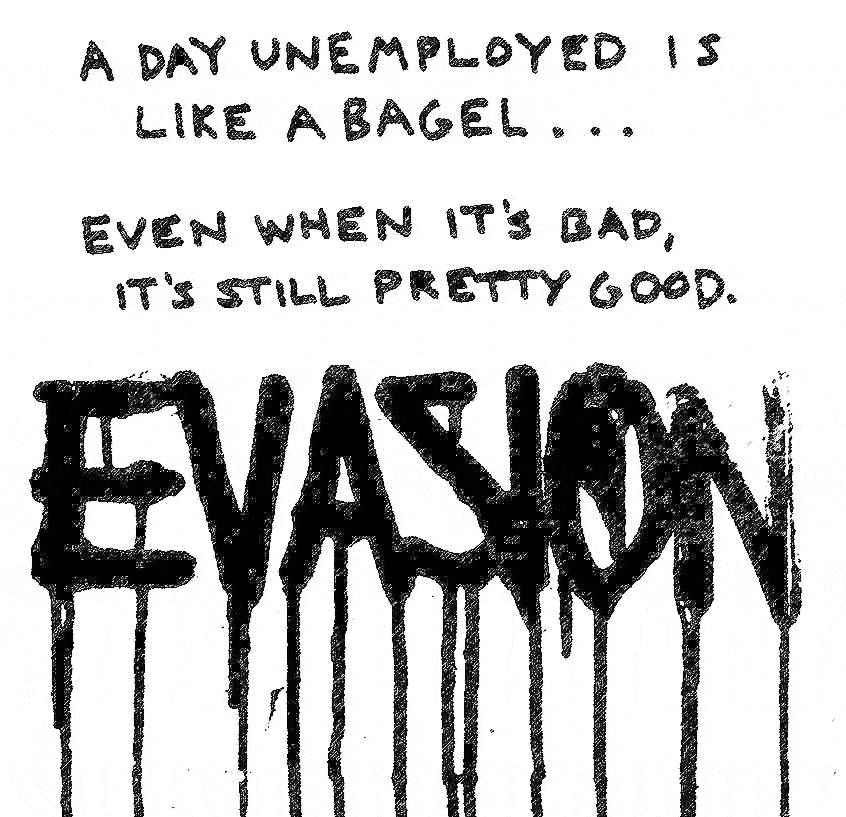

Although similar sentiments are perhaps implied elsewhere in the Crimethinc canon, this phrase was taken from an image of a defaced billboard printed in the anonymously written travel memoir Evasion. The cult classic tells the story of a young straightedge vegan anarchist who hitchhikes, dumpsters food, scams Wal-Mart for petty cash, sleeps in libraries and movie theaters, squats, couch-surfs, and seamlessly lives his political ethics while doing so. The book convinced untold thousands of millennials to drop out of college, put on a big backpack, and hit the road or the rails. These “travelers” made up a network of summit-hoping black-blocers, squatters, animal liberators, antifascists, culture-jammers, prison abolitionists, and eco-sabotaging elves, dedicated to exiting the world and fucking it up as much as possible on their way out.

But this generation also gave many the impression that anarchists were Peter Pans oblivious to their various forms of privilege. Could many other than white cis males live such a charmed hobo life? And for the hundreds of thousands of Americans homeless by circumstance, not choice, isn’t this deeply insulting?

While many of the same sort of questions can be asked of Nomadland, it cannot be ignored how inspirational such lifestyles can be to both suburban teens and aging workers alike, a fact not unnoticed by the film’s best supporting actor: the Amazon corporation.

Recipes for Disaster

Like the Evasion guy, Fern finds community in the fellow van-dwellers who share skills and emotionally support one another at various meetups throughout the year. The communal life in these camps, and the romantic spirit of its founder Bob Wells, looked almost like the Crimethinc convergences with its participants suddenly aged several decades.

The major difference is that the old-timers are not evading work, but constantly chasing it—the utopian rendezvous was only a reprieve within Fern’s permanent working-vacation. The rest of the film shows her overseeing industrial agricultural, working at a truck-stop diner, hosting campers at a national park, and packing boxes at the Amazon fulfillment center where the film begins and ends.

Although cinematographer Joshua James Richards told The Wrap that they had approached Amazon, and the scenes were meant neither to be a “celebration nor a condemnation”, the mega-corporation likely could not have been happier with the result. As it battled against unionization early this year, the must-see film was released with a depiction of Amazon as a safe, lucrative, and socially beneficial community for Fern and her fellow nomads. The opening montage—in which Fern is given safety training by a friendly team leader amidst an enthusiastic staff before a lunch break leisurely enough for a quirky coworker shows-off their Morrissey tattoos—could have been written by the same team now waging a ham-fisted PR campaign denying its perilous labor conditions. At multiple points in the film Amazon is referred to as a well-paying and dependable place to return when the goings get tough for Fern, Amazon becomes the film’s hero.

The hero of the movie should have been Swankie, the grizzled van dweller badly injured after a work-related accident. She befriends Fern and teaches her some important survival tips for van life before revealing that she has terminal cancer, and plans to forego treatment to spend her last days in the Alaskan wilderness. During a long contemplative montage, it seems as though the idea of this woman dying alone in the woods might challenge Fern’s commitment to live in a van and work until her body gives out. Instead, it reaffirms her faith in the beauty of doing just that.

The most powerful aspect of the film is that many of the nomads and workers Fern encounters are real people playing themselves. Fern, however, is pure fiction. McDormand told Vogue the character was based on her long-running drop-out fantasy: “When I’m 65, I’m changing my name to Fern, I’m smoking Lucky Strikes, drinking Wild Turkey, I’m getting an RV, and hitting the road.” Even with my nostalgia for the anarcho-traveler lifestyle, this fantasy stuck me less as the romantic last days of an American free spirit than the catchphrase of Matt Foley, Chris Farley’s motivational speaker character from Saturday Night Live, who scared teens straight by warning them that they could end up, like him, living in a van down by the river.

This is not say Fern isn’t believable. While the world expects a poor, aging widow to be desperate, crushed by loneliness, haunted by lack of children or some other regret, it’s reasonable to imagine her satisfied with the seasonal friendships of coworkers and fellow nomads, disinterested with remarrying or reconnecting with her family, and even perfectly happy with an annual stint of hard warehouse work. It’s not so different, after all, from the Crimethinc travelers who punctuated ten months scamming, squatting, and couchsurfing with two months trimming weed or canning cranberries.

And maybe that’s not a coincidence. The logic behind the “you’re not doing it right” line, however ill-conceived, was never meant to disparage those who are homeless, but to defend those who are happier refusing social expectations.

The romance is troubled when the nomad life isn’t a choice. Homelessness has been slightly rising in the United States since 2018, with an increase in the percentage of those homeless people without shelter jumping from 30% in 2015 to 37% in 2019. These unsheltered homeless often concentrate in places like New York, the Bay Area, and Los Angeles, leading to brutal backlashes against the appearance of the sorts of camps celebrated in Nomadland.

Much of this population, Bruder wrote, were produced by the 2008 crash and its aftermath. The price of living has only continued to rise to the extent that even full-time Amazon employees are having trouble affording housing. Calling for more funds for better social safety nets, tenant protections, social services, and transitional housing, homelessness advocates have long pointed to numbers like these as a worsening crisis. Amazon, on the other hand, saw opportunity.

As Amazon’s logistics scaled-up in the mid-2000s the company found themselves scrambling for temporary workers during the holiday high season. In 2008, Bruder wrote for Wired magazine, they experimented by inviting a “a team of migrant RVers” to work in a Kansas facility. It was such a good match they created a new hiring initiative for warehouses across the country called CamperForce.

Many of the workers who joined CamperForce were around traditional retirement age, in their sixties or even seventies. They were glad to have a job, even if it involved walking as many as 15 miles a day on the concrete floor of a warehouse. From a hiring perspective, the RVers were a dream labor force. They showed up on demand and dispersed just before Christmas in what the company cheerfully called a “taillight parade.” They asked for little in the way of benefits or protections. And though warehouse jobs were physically taxing—not an obvious fit for older bodies—recruiters came to see CamperForce workers’ maturity as an asset. These were diligent, responsible employees. Their attendance rates were excellent.

In internal seminars the company bragged that by 2020 a quarter of “workampers” like Fern would have passed through CamperForce—some aged above 80.

The integration of this demographic not only helps fill gaps in human capital, it becomes an excellent talking point to deflect the unionization efforts of Amazon’s massive manual workforce. Amazon’s $15 starting salary may sound more than fair for a low-level job akin to temp work, service work, retail, or the kindly old Wal-Mart greater. In reality these jobs are closer to more stable, labor intensive, and dangerous ones popularly believed to deserve higher pay and benefits, like truck-driving or assembly line manufacturing.

The image of “retirees” happily working at Amazon also provides the basis for another, arguably even more sinister restructuring. It was once thought that hard work was for the young. Some decades of hard labor earns a retirement so the last years of life can be fully enjoyed. For the workampers, that enjoyment comes through the fulfillment center. Meanwhile, urban young idolize the life of the digital nomad—telecommuting on their own schedule from an AirBnB in Tulum or Thailand where rent is cheaper than most hip areas of New York or LA. The comparatively lower pay and benefits of these careers than those of their parents is compensated for the personal austerity of foregoing a spouse and children, living with roommates or chosen family instead. Homeownership may be totally out of the question, but at least they can afford the best bagels and granola money can buy.

Days of Twitter, Nights of Tinder

Cringey as they may seem today, the early works of Crimethinc represented the avant-guard of revolutionary political thought for the Gen-X era. Books like Days of War Nights of Love and Recipes for Disaster brought the non-conformist attitude of the new left and the anti-right-wing/corporate politics of the eighties/nineties into a new youth movement willing to take the offensive in a scale unseen since the sixties But just as the boomers’ failure permitted their libertine gains recuperated for neoliberal superstructure, the lifestyle anarchism of the oughts has been ceded to Silicon Valley marketers who glorify the brutal austerity of the working class as “flexibility” and the anti-worker disruptor apps a “sharing” economy.

This is not to say they are to blame for our technodsytopia. Unlike most of the left, Crimethinc never sought a new sort of economy. Their goal was to abandon it as much as possible, taking whatever they could stuff into their messenger bags on the way out, sharing the goods at the squat to prove the good life came not from exhaustive work and consumerism, but by getting free immediately, and freeing others to come with you.

If the Crimethinc generation grew up, started businesses, became investors, academics, dirtbag podcasters, etc., it’s not necessarily because they changed, but that the world hasn’t. Like the sixties rebels, they made their cultural revolution short of the point of no return. It took police little time to develop the Miami Model to neutralize the summit-hopping black blocers, and the Green Scare to chill earth liberation. Once a real estate bubble killing squats since the eighties finished the job in the oughts, there was nowhere left to go.

From its first pages, Evasion saw this coming:

Something happened when we quit our jobs, quit paying rent, quit paying for anything… They said, “You can’t live this way forever.” Some of us agreed, and secretly planned to leave youth behind one day. Others thought — “We’re good now, in ten years we’ll be pros, in twenty we’ll conquer the world!” Some hoped not. They wished people wouldn’t throw so much away — food, books, whole buildings. That one day the means of production would be returned to the people so we wouldn’t need their food, or their old houses. They made the mess, may as well dance in it. Some of us shrugged and said, “Why not?” Others found the implication odd that they could live their way forever — working and drinking and watching TV — and why they would want to.

A well-worn joke in anarchist circles paraphrases the next lines:

Q: How many Crimethinc kids does it take to screw in a lightbulb?

A: Those first moments... A new house, a new life... Artists, vandals, philosophers... Up on our favorite rooftop, with a view of the city, passing dumpstered granola and thinking — If we can change this lightbulb, we can change the world.

The joke summarized the perceived naivety of Crimethinc. How does quitting your job and eating trash change anything? Other anarchist measures, like street trashing and squatting, were seen as equally deluded. But that’s an old criticism, one that Minor Threat had long ago sufficiently answered: At least I’m fucking trying. What the fuck have you done?

Much like political hardcore, Crimethinc eventually succumbed to the changing times. After the financial crisis, they changed their tone, ditching the travelogues and punk zines for more theoretical books with names like From Democracy to Freedom and Work. Evasion became a taboo subject. A final convergence in 2009 ended prematurely after a group of anarchist people of color disrupted it for being a “breeding ground for white anarchists… [who] encourage the culture of dropping out of society, which makes the assumption that the reader/attendee has that privilege and therefore their words speak only to those that have it.” The culture of dumpster diving, train hopping, and Food Not Bombs became popularly synonymous with the irresponsible “oogle” crustpunks presumed by all to be secretly wealthy trust funders. Counterculture was no longer an end in itself. Changing the world no longer meant simply changing ourselves, let alone a lightbulb.

Their era ended before it ever truly arrived. An anonymous critic writing after Occupy described the change: “[M]uch like the spineless jellyfish that goes wherever the sea takes it, Crimethinc has now abandoned the anarchist identity of eating out of the garbage can for the anarchist identity of burning garbage cans…” The late folk punk Erik Peterson lamented in his song “Nomad’s Revolt": “Swore we'd carry on like this forever/'til the free spirits fled/Now can you believe who's a mother/And that so-and-so's cut of their dreads?”

No matter how passé, the autonomous zones of hippie festivals, ’68 riots, rural communes, punk houses, Occupy camps, tent cities, the CHAZ, and the workamper rendezvous of Nomadland all share the same allure—a reprieve from the everyday life we are forced to live, created by those ready to leave it. In the eternal struggle of capital to adjust itself to these emerging forms of dignified living against the misery it creates, capital today resorts to CamperForce, SalesForce, or brute force of riot cops and bulldozers. Evasion guy and McDormand’s were both wrong to imagine a lone free-spirited dropout could meaningfully survive these forces. Organizing to both refuse work and fight the forces demanding our return was Crimethinc’s resolution. Nomadland, on the other hand, is less Kropotkin than Kevorkian.